Artificial intelligence has become a powerful accelerator in game development. In iGaming, AI-assisted tools help studios reduce costs, shorten production cycles, and deliver familiar, polished experiences to market faster than ever. At the same time, these same tools have amplified a long-standing industry challenge: the rise of look-alike games that closely imitate the style, mechanics, and overall “feel” of successful products without directly copying them.

This dual nature of AI creates a new risk landscape. While AI-driven efficiency can be a competitive advantage, it also blurs the line between inspiration and imitation, exposing operators and suppliers to legal, regulatory, and commercial uncertainty — especially in a highly standardised and regulated industry like iGaming.

In this article, Dmitry Smirnov, EvenBet’s Senior Lawyer, and Darya Korshunova, Junior Legal Counsel, examine the issue from a legal perspective. They provide an overview of how AI-generated and AI-assisted game assets are treated under current copyright and competition frameworks, and outline practical considerations that can help iGaming businesses navigate this evolving area and avoid costly legal and regulatory consequences.

AI-Assisted Game Development and the Look-Alike Problem

Artificial intelligence has evolved from an experimental novelty to a common production tool in game development. AI-assisted workflows are now widely used by studios for everything from concept art and animations to sound effects, UI mock-ups, balancing simulations, localisation, and dialogue generation. These tools are especially appealing in the iGaming industry, where cost effectiveness and speed to market are crucial. A small team can now generate a polished visual layer, functional interfaces, and familiar mechanics in weeks rather than months.

At the same time, AI has scaled up a long-standing problem in the gaming industry: the creation of similar or cloned products. A “look-alike” game is not a literal copy of code or assets, but a product that closely mimics the visual style, user experience, mechanics, and overall “feel” of a successful title. For traditional development, cloning took serious effort and skill, but with Generative AI, imitation is speedier, less expensive, and more scalable.

The iGaming industry is uniquely vulnerable. Poker tables, card designs, slot interfaces, animations, and UX flows are already highly standardized. Regulators demand consistency, and players prefer games that feel familiar. AI tools trained on existing games can quickly produce interfaces and assets that feel almost identical to well-known brands, without copying any single file verbatim.

This raises a difficult legal question: when is AI content simply “inspired by” an existing game, and when does it cross the line into being too similar? Existing copyright and competition laws were not designed for AI-generated content that blends styles at scale. As such, the present situation is being felt to fall into a gray zone that is fraught with commercial risk.

Requirements for Human Authorship

EU: “Author’s Own Intellectual Creation”

Under EU copyright law, protection requires that a work be the “author’s own intellectual creation.” This standard, developed through CJEU case law, focuses on human creative choices reflecting personality and free expression. Purely mechanical or automated outputs typically fail this test.

For AI-generated content, the challenge is attribution. If no human can be said to have made the creative choices embodied in the output, copyright may not subsist at all. This does not mean the content is “free to use” in practice — it means there is no clear rights holder to enforce exclusivity.

The user’s input typically lacks sufficient creative contribution, while the developer does not control outputs of it. The “producer” model (such as the UK approach to computer-generated works) is also impractical for generative AI due to the difficulty of identifying the person responsible for the creation of a specific output – therefore, such content might have too many possible authors to choose from.

Malta: EU Framework, Practical iGaming Relevance

Malta, as a key iGaming jurisdiction, follows the EU framework. From a licensing perspective, this creates practical issues rather than theoretical ones. Operators are expected to demonstrate ownership or licensed rights in their game assets. If a significant portion of a game’s visuals or UI is AI-generated with unclear authorship, regulators may question whether the operator can genuinely control and protect its product.

UK: Section 9(3) CDPA and Its Uncertainty

The UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act contains a special provision: for “computer-generated works,” the author is deemed to be “the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken.” This appears, on its face, to accommodate AI-generated output.

However, the provision predates modern generative AI and has been lightly litigated. It is unclear how much human involvement is required, how “arrangements” are defined in complex AI pipelines, and whether this provision remains fit for purpose. The UK government has repeatedly consulted on reform, adding further uncertainty.

US: Human Authorship Requirement

In the United States, the position is clearer but more restrictive. Copyright protection requires human authorship as demonstrated in cases involving Stephen Thaler and the AI system DABUS. The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed that only a natural person could be an inventor, which means that the AI that invents any other type of invention is not addressed by the “who” mentioned in the legislation.

At the same time, the US Copyright Office’s guidance for 2023–2024 reinforces that works entirely created by AI, without sufficient human creative control, are not registrable. Human selection, arrangement, or modification may be protectable — but the AI-generated elements themselves are not.

Why This Creates Commercial Risk

Across jurisdictions, autonomous AI outputs often fail to attract copyright protection. This does not create legal certainty — it creates exposure. If your AI-generated assets are not protected, then competitors might be able to reuse or closely imitate such assets with relatively low legal risk. At the same time, you may still face claims that your outputs infringe someone else’s rights or constitute unfair competition. The asymmetry is commercially dangerous, and the legal decision is unpredictable.

AI as a Tool vs AI as an Autonomous Creator

The Legal Distinction

Lawyers and regulators are now applying this important difference between AI used as a tool and AI used as an autonomous creative entity. In AI-assisted creative works, humans are in charge and generally direct and control creative decisions. In autonomous AI creative works, AI outputs are generated with minimal human intervention.

This is germane to consider, particularly since copyright attaches to creativity, not to processes. Indeed, the more autonomous a computer program, the less it claims copyright.

Evidentiary Problems

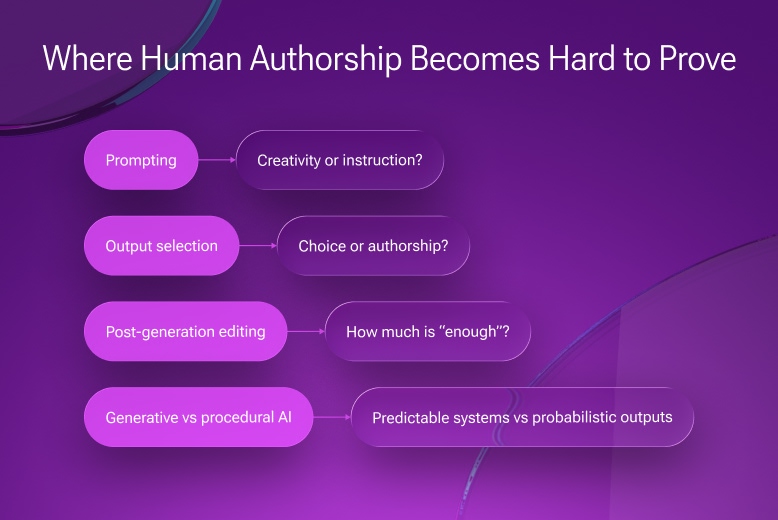

In practice, drawing the line proves to be quite difficult. For example:

- Prompting: is the act of providing a clear, detailed prompt an act of creativity, or an act of instruction?

- Iterative Selection: does selection of one output from many constitute an activity that constitutes authorship?

- Post-generation editing: how much editing does it require before the human aspect is prominent?

- Procedural versus Generative Systems: Procedural systems are familiar and predictable in game development. Generative AI systems, however, rely on probabilities, which makes their behavior harder to measure and control..

In cases of iGaming studios, documentation of human involvement is crucial from both copyright and regulatory compliance points of view.

Relevance for iGaming

Common AI Use Cases

AI is increasingly used to generate or assist with:

- Visual effects and lighting

- Animations and transitions

- Poker table layouts and felt designs

- Card backs, icons, and chips

- UI/UX patterns and lobby flows

- Slot or poker-adjacent mechanics and feedback loops

Individually, these elements may not be protectable. Collectively, they define a game’s commercial identity.

Style as a Commercial Asset (Legal Weakness)

“Style” is immensely valuable in iGaming. Players associate trust, fairness, and quality with familiar visual languages. Yet style, as such, is rarely protected under copyright. The reason is that copyright will protect expression but will not extend to ideas, systems, or styles.

This presents a paradox in that it allows the best parts of that game, i.e., AI, to reproduce without borrowing any of these protected elements.

The ongoing case Andersen v. Stability AI raises unresolved questions about whether using copyrighted images as training data infringes authors’ rights, particularly where AI systems enable generation “in the style of” specific artists. Individuals have used AI Image Products to create works using the names of Plaintiffs and the Class in prompts and passed those works off as original works by the artist whose name was used in the prompt.

Artists in this case claim not only the copyrights protection, but the violations of the contract (Term of Use), as the legal practice is more familiar with such demands. The final decision has not been announced yet, but considering that the court has already sided with Stability AI by saying the legal standards simply aren’t met under current law, we can suppose that the copyrights protection will not be achieved fully.

Judges in related cases have been cautious about imposing sweeping liability for training AI models, especially where the plaintiff can’t show exact copies or clear unauthorized reproduction. Courts have demanded specific evidence of copying and precise legal theories, not just broad arguments about training data.

Market Substitution and Regulatory Attention

Cases involving issues like training data and how generative AI works are legally unsettled, meaning judges don’t have clear precedents to apply. In such instances, regulators or platform holders may step in. If the clone is deemed confusing, or if it dilutes brand differentiation, or if it’s considered unfair, it could be problematic notwithstanding copyright considerations. In the case of regulated gaming sectors, there’s potentially more at play than decisions relevant to litigation outcomes.

The recent example of platform self-regulations is the American corporation Valve, owning a famous gaming platform Steam. In August 2023, Valve reportedly adopted policies of rejecting games that include AI-generated assets where developers cannot clearly demonstrate ownership of the underlying intellectual property.

A game developer disclosed that Valve refused to publish his game on Steam because it contained AI-generated art that may have been trained on copyrighted third-party works. Even after modifying the assets to remove visible AI traits, the game remained rejected.

Required Research Integration

AI Training on Gameplay and Assets

Irvin, Taube & Choi’s analysis highlights that AI systems increasingly train on gameplay videos and recorded sessions. Whether this training constitutes copyright infringement remains unsettled. After Google v. Oracle and Warhol v. Goldsmith, fair use analysis is highly contextual. Transformative purpose helps, but market substitution weighs heavily against fair use.

“Style imitation” is particularly hard to litigate because copyright does not protect style itself. As a result, contract law — EULAs and Terms of Service — has become the strongest protection. Game publishers can prohibit scraping, training, or reuse of assets by contract.

However, contract enforcement has limits: no DMCA-style takedowns, privity issues, and cross-border enforcement challenges. For iGaming operators, this means contracts are necessary but insufficient.

Clyde & Co: AI Disputes Rarely Stay in Copyright

Clyde & Co’s work emphasizes that AI disputes span multiple regimes: copyright, labor law, personality rights, and consumer protection.

The dispute with AI-generated voices, such as the well-known Fortnite/Darth Vader case, underscores how quickly such cases can escalate beyond intellectual property into personality rights, labor law, and consumer protection, particularly where audiences believe a real person has endorsed or participated in the experience.

As industry commentators noted at the time, the controversy was less about ownership of recordings and more about control over voice, identity, and consent.

Similar dangers can develop in iGaming as far as dealer likenesses, voices, and experiences. Even if copyright fails, other claims may succeed.

Yang & Zhang: The Dynamic Perspective

Yang & Zhang’s “double-threshold” model explains why mid-skill creators are most affected by AI. High-end studios have the option to invest in originality, whereas low-end creators rely completely on AI. Mid-tier creators resort to AI with the aim of being competitive.

Data availability, not doctrine, becomes decisive. Those with access to large datasets can produce convincing clones regardless of legal uncertainty. Training may be legal even if outputs are not protected by copyright due to the asymmetrical relationship between fair use and copyrightability: using copyrighted works to train an AI might be allowed, even if the AI’s outputs can’t be copyrighted themselves.

This puts structural pressure on AI middleware providers, game studios, and asset marketplaces to homogenise.

GitHub Copilot VS OpenAI (U.S., 2022)

In 2022, a group of software developers filed a class-action lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California against GitHub, Microsoft, and OpenAI, alleging unlawful use of their open-source code to train the AI tool GitHub Copilot.

The plaintiffs claim that their source code, published on GitHub under various open-source licenses was used to train Copilot without complying with license requirements, particularly: failure to provide attribution to original authors, removal or omission of license texts and use of licensed code in a commercial AI product without respecting license conditions. They also allege that Copilot can generate code outputs that are substantially similar to, or in some cases replicate, original copyrighted code, raising concerns of copyright infringement rather than mere learning or transformation.

The defendants argue that training AI models on publicly available code constitutes fair use and does not require compliance with individual license terms.

The case has not been finally resolved on the merits, but the court allowed several claims to proceed. This indicates that the legal questions surrounding AI training on licensed content are unsettled and legally significant.

Practical Takeaways for iGaming Businesses

Style is economically vital in video games — and legally fragile. AI entrenches this asymmetry by rendering stylistic cloning inexpensive, swift, and scalable. Existing legal instruments cannot keep pace, with studios exposed on both sides: unable to fully safeguard their own AI-assisted assets on the one hand, and open to claims from others on the other.

For B2B iGaming operators, the way ahead is pragmatic, rather than doctrinal:

- Using AI as a tool rather than autonomous creator: ensure that humans make and document key creative decisions, including selection, refinement, and modification of AI outputs.

- Contractual controls: unambiguous EULA, agreements of suppliers, and restrictions on AI use. Contract law is currently the strongest tool to protect IP rights, despite not weaker remedies (no DMCA takedown).

- Compliance: Compliance with a conservative disclosure and provenance standard out of the box.

- Internal AI Governance: Documentation of human input and training data sources and creative decision-making.

- Avoid reliance on “Style” as a protective asset to protect copyrights: Style is commercially powerful but legally fragile. To reduce cloning risk, the best way is to invest in distinctive combinations of elements (visuals, audio cues, pacing, interaction logic), rather than relying on any single stylistic feature.

AI will not eliminate clone games — but disciplined legal and operational strategies can reduce risk and preserve long-term value. For iGaming businesses, the winners will not be those who imitate fastest — but those who combine speed with defensible originality and regulatory credibility.