Gambling is often described through numbers, mechanics, and regulations — but behind every game lies a cultural and emotional logic that is just as important. Philosophers and sociologists have spent decades exploring why people take risks, how they perform identity, and what makes certain moments of play feel so real.

This article brings those ideas into the world of online gambling, but without academic jargon or theoretical detours. Instead, we translate these perspectives into clear, practical insights that help operators see their products from a new angle. The goal is not to simplify complexity, but to make it useful.

A Simple Introduction to Simulacra and Hyperreality

Philosopher Jean Baudrillard argued that late capitalism is full of simulacra — copies that no longer point to any original reality. They don’t imitate the real world; they imitate our ideas about the real world. And once a copy becomes more vivid, more stylized, and more emotionally charged than the thing it imitates, we enter what Baudrillard called hyperreality.

This may sound abstract, but the easiest way to understand it is through pop culture.

Take Stranger Things. The Netflix series doesn’t recreate the 1980s as they actually were — it recreates the memory of the 1980s shaped by movies, games, and cultural fears of that time. The show gives us neon colors, synth music, mall culture, and Cold War paranoia, all turned up to eleven.

Another great example is the music genre retrowave (or synthwave). It sounds instantly recognizable as “80s music” — warm analog synths, nostalgic melodies, chrome-shiny beats. But here’s the twist: music with this exact aesthetic did not exist in the actual 1980s. Retrowave is a modern creation that captures what we think 80s music sounded like, based on movie soundtracks, arcade memories, and cultural nostalgia. It’s a tribute to a past that never truly happened.

If we compare Stranger Things or retrowave tracks to authentic films and songs from the 80s, something becomes clear: these modern works contain more 80s-ness than the 80s themselves. This is hyperreality. It’s when a stylized version of the past becomes more vivid, more emotionally satisfying, and more familiar than historical reality. The copy overtakes the original.

How Gambling Constructs Its Own Version of Reality

We can see the same logic of simulacra and hyperreality at work in the gambling industry. A casino is not just a building with games — it is a carefully directed environment that feels more real than everyday life. Everything in it, from lighting to sound to the layout of the floor, is designed to create a sense of intensity, clarity, and emotional focus that ordinary reality doesn’t offer.

Goffman — Gambling as Performance

Sociologist Erving Goffman famously described everyday life as a form of theater, with people constantly performing roles. In his early years he worked as a dealer in Las Vegas, and many of his observations about performance and risk come directly from that environment.

Poker, in particular, served for him as a perfect stage. In his 1967 essay “Where the Action Is”, Goffman shows that players do not simply wager money — they wager identity. A poker hand tests a person’s ability to stay composed, manage impressions, project confidence, and recover dignity after loss. The risk is both financial and social.

Through this lens, a poker table becomes a small theater of self-presentation, where the currency is not just chips but control, image, and emotional discipline.

Reith — Gambling as a Ritual and a Way to Face Uncertainty

Sociologist Gerda Reith connects the rise of modern gambling with the decline of clear social structures and predictable life paths. When traditional sources of meaning weaken, people turn to activities that offer direct encounters with uncertainty — and gambling does this in a highly ritualized, emotionally satisfying way.

Drawing on cultural theory, Reith describes gambling as a form of deep play: an activity that helps people symbolically rehearse the randomness of life. The rituals of betting, anticipating, and reacting to outcomes create a controlled space where chaos feels manageable.

Cassidy — Gambling as a Social and Political System

Anthropologist Rebecca Cassidy conducted long-term fieldwork in betting shops, racing tracks, poker communities, and gambling companies. Her conclusion is clear: gambling is not an isolated personal pastime. It is a network of social, economic, and political relationships, and the player is embedded within that structure.

In Cassidy’s view, players:

- learn and perform roles,

- build identities,

- and construct narratives about themselves — being “strategic”, “lucky”, or “rational”.

These identities do not emerge spontaneously. They are shaped by the design of games, the behavior of other players, the surrounding culture, and even by operators’ marketing and platform mechanics.

Gambling, therefore, is not simply an individual choice; it is a social environment that teaches people how to interpret chance, risk, and their own actions.

Poker as a Mirror of Capitalism — Through the Lens of Ole Bjerg

These ideas connect directly with the work of Danish sociologist Ole Bjerg, who explored poker as a cultural and economic phenomenon in his 2011 book Poker: The Parody of Capitalism. Bjerg argues that poker doesn’t just resemble a market — it recreates one.

A poker table, in his interpretation, contains the full logic of capitalism in miniature:

- investment (the buy-in),

- speculation (the bluff),

- information asymmetry,

- risk management,

- sudden bankruptcy,

- redistribution of resources.

Poker becomes a theater of capitalism — a condensed, transparent version of how competition, risk, and inequality actually operate.

Money in Poker — From Social Symbol to Pure Risk

Building on the ideas of philosopher Slavoj Žižek, Bjerg highlights an important shift. In everyday life, money carries layers of meaning: it represents labor, status, responsibility, and security. But at the poker table, money loses these symbolic attachments and becomes a pure token of risk — something that matters only within the closed world of the game.

This abstraction makes the game feel strangely honest. Žižek noted that fantasy can sometimes reveal truth more clearly than reality, and Bjerg applies this directly to poker:

- In real-life capitalism, people are encouraged to believe that effort leads to success.

- In poker, everyone openly acknowledges that success also depends on luck.

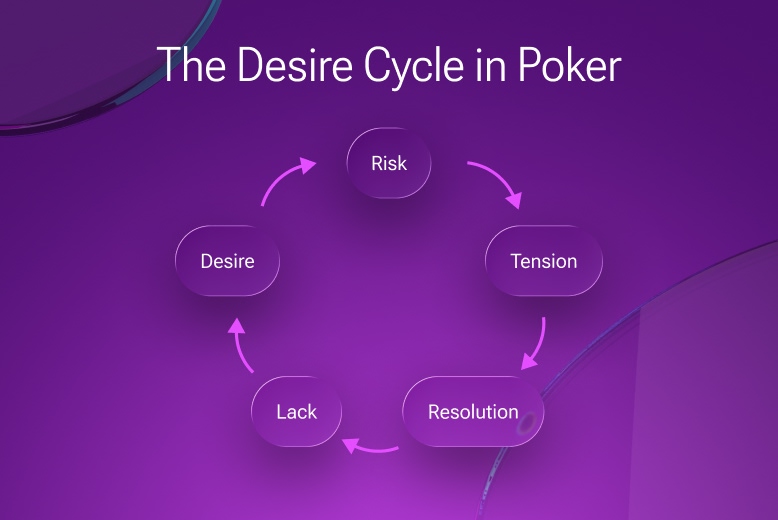

Desire, Lack, and Jouissance — The Emotional Engine of Poker

Bjerg also draws on the ideas of French philosopher and psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who argued that human desire is never fully satisfied. We always want “something else”, because any object of desire slips away the moment we approach it. This built-in sense of incompleteness — what Lacan called lack — keeps us moving, trying, chasing.

Lacan also introduced the concept of jouissance — a form of pleasure that mixes excitement with discomfort, pain, or risk. It is the thrill that pushes us beyond rationality.

Seen through this lens, poker becomes a laboratory of desire:

- every decision creates a new sense of lack,

- every risky move brings a spike of jouissance,

- every lost pot triggers the urge to “win it back” — not because the player needs the money, but because the psychological cycle demands closure that never arrives.

The game continuously restarts the loop of wanting, risking, losing, recovering, and wanting again. It is not simply entertainment; it is an emotional system built around tension, anticipation, and the search for an unreachable moment of complete satisfaction.

How Online Gambling Amplifies the Logic of Hyperreality

The philosophers we discussed earlier explored gambling mostly through the lens of physical casinos and in-person play. Yet the most striking expression of their ideas appears not in land-based establishments, but in online gambling, where experience becomes cleaner, sharper, and more stylized than reality itself.

Traditional casinos attempt to reproduce aspects of the real world — especially the logic of markets and competition. Online casinos, however, are simulacra of casinos. They are not based on how actual casinos look or function, but on how casino spaces live in the imagination of players. In this sense, an online casino is often more of a casino than a physical one.

Live Casino — A Polished, Idealized Version of the Real Thing

Consider one of the most popular formats in modern iGaming — live-dealer casino, where a real human dealer is streamed from a studio in real time.

In a physical casino, the environment is full of friction:

- noise,

- crowds,

- cigarette smoke (in some regions),

- dealers with varying levels of skill and professionalism,

- uneven or dim lighting,

- visual and auditory clutter.

A live-casino studio strips all of this away. Instead, players see:

- perfect lighting and clean, cinematic shadows,

- carefully selected dealers with polished speech and appearance,

- a fully controlled soundscape with no background noise,

- a professional camera setup with ideal angles and depth of field.

Operational processes, which are visible in land-based venues, remain hidden. The player sees only the “show”, not the machinery behind it. Everything that might distract, irritate, or break the illusion of exclusivity is removed. All elements of unpredictability and chaos — except for the randomness of the game itself — are filtered out.

The result is an experience that feels cleaner, more aesthetically refined, more convenient, and more predictable than any real casino floor.

In philosophy, this is often described as simulated perfection — an improved, stylized version of reality. In Baudrillard’s terms, live casino becomes a simulacrum: an idealized representation that feels more real than its real-world counterpart.

Card Squeeze — Bringing Physical Drama Into a Digital Environment

Online poker also adopts and amplifies real-world rituals. A good example is the Card Squeeze feature, where a player reveals their hole cards slowly, lifting the edges as if holding real cards.

In this moment, the player is not simply playing poker — they are playing the role of someone who plays poker. The feature lets them inhabit the fantasy of live play, performing the familiar physical ritual even though no real cards, table, or dealer exist. It is a small piece of theater inside a digital game, and it strengthens the emotional authenticity of the experience.

On a sensory level, the feature does even more:

- a hyperreal simulation of touch and tension,

- a brief moment of drama before the reveal,

- a feeling of physicality in a space that has no physical elements.

Psychologically, this works because the gesture introduces a sense of control, even if the outcome is entirely predetermined by the random number generator.

That tiny pause — the breath before you see your cards — is a core component of gambling pleasure. And paradoxically, a digital simulation of the gesture can feel more real than an actual card, because it is perfectly staged and emotionally targeted.

Dealer Tips — A Social Ritual Without a Real Recipient

Another example is the Dealer Tips feature, which allows players to give virtual tips to the dealer. In some cultures, tipping is believed to increase luck, making it not just a social gesture but a small ritual of fortune.

In a real casino, tipping is a meaningful act of recognition. Online, there is no dealer at all — yet the ritual persists. Players know that no human is handling the cards or responding to their gesture, but they still perform the act because the meaning of the ritual outlives its original purpose. The gesture loses its practical function, yet retains its symbolic power.

Symbolically, this becomes:

- a classic Baudrillardian “sign without a referent”,

- a voluntary performance of sociality,

- a way to feel part of a shared space even when playing alone.

Psychologically, it works because small voluntary payments feel good. They provide:

- a micro-ritual of generosity,

- a harmless, emotionally comfortable way to spend a little extra,

- a sense of presence in a social environment.

From a cultural perspective, Dealer Tips act like a ritual tax on participation — a symbolic fee players pay to inhabit the role of a casino participant. They are not paying for a service; they are paying for the feeling of being part of a real gambling scene.

What It All Means for Operators

For someone outside sociology or philosophy, all these ideas may seem like an intellectual warm-up — interesting, but distant from real business. Yet they offer surprisingly practical insights for operators of online casinos and poker rooms. These perspectives can help teams rethink product decisions, refine UX, and shape strategic choices with a deeper understanding of the player experience.

1. You Are Creating Not Just a Game, but a Stage and a Role

As Goffman, Bjerg, and Cassidy each suggest in their own way, players are not simply placing bets — they are performing identities:

- the smart strategist,

- the lucky high roller,

- the calm professional,

- the outsider “playing against the system”.

This means the digital environment should make it easy for players to step into a role.

Design UX and visuals not only for clarity, but for performance. Avatars, nicknames, statuses, achievements, and even small customization options are not cosmetic extras — they are tools of self-presentation. The easier it is for someone to “play themselves”, or the version of themselves they aspire to, the stronger the engagement and the higher the loyalty.

2. Rituals Matter More Than You Think — and They Should Be Designed Intentionally

Card Squeeze, Dealer Tips, chip-stack animations, soft delays before reveals — these are not minor embellishments. They are rituals that:

- give players a sense of control,

- structure emotional peaks,

- create the feeling of “real play”.

Prioritize rituals, not only speed. Extremely fast, sterile UX can break the emotional arc of the game. Think about which offline gestures can be meaningfully translated into digital form — and check regularly whether any features unintentionally disrupt these micro-rituals.

3. Players Do Not Return for Wins Alone — They Return for the Desire Cycle

Lacan, Žižek, and Bjerg all highlight the same mechanism: people are driven not by outcomes, but by desire, which renews itself through tension and release.

Over-optimized speed can flatten the emotional landscape. Consider where the game creates anticipation, where the “micro-drama” lives, and how each feature supports meaningful tension. Even promotional messaging can reflect this: focus not only on jackpots, but on quality of experience, rhythm, story, and emotional pacing.

4. Online Gambling Is Hyperreality — So Aim for Better Than Real

Baudrillard’s idea of hyperreality becomes practical in iGaming. A successful product is not a literal digital replica of a casino — it is a refined, idealized version of one.

Do not copy offline environments literally. Create a version that is cleaner, smoother, and more cinematic. If a detail from real life doesn’t translate well, remove it. Realism in online gambling is not about accurately simulating a carpet texture — it’s about emotional plausibility: clarity, immersion, and a feeling of controlled tension.

5. Money in Online Gambling Is a Pure Symbol — Both an Opportunity and a Risk

Bjerg points out that in poker, money becomes a token of risk rather than a symbol of labor or status. In online gambling this abstraction becomes even stronger: the balance is simply a number on a screen.

UI that makes money too abstract increases overspending risks — ethically and regulatorily. Designers can intentionally “return weight” to money: clear deposit reminders, visible limits, session timers, transparent histories. Long-term trust grows when money feels understandable and manageable, not like an infinite digital resource.

6. Dealer Tips and Similar Features Are About Belonging, Not Monetization

Online tipping is a pure simulacrum — a gesture without a real recipient. Yet players use it because it reinforces the role of being “in a casino”, offers a small moral reward for generosity, and in some cultures is even believed to bring luck.

Treat such features as tools for social atmosphere, not as small revenue levers. They signal participation and belonging. Overuse, however, risks breaking trust — if the feature feels manipulative (“tip again for more luck”), the emotional contract collapses.

Conclusion

Online gambling is not just a digital version of the casino — it is a hyperreal environment built from rituals, roles, and emotions that players bring with them. From Goffman’s idea of performance to Bjerg’s reading of poker as a miniature market and Lacan’s cycle of desire, the industry reveals itself as a cultural stage where people experiment with identity, risk, and control. Digital products amplify these dynamics by offering perfected, stylized experiences that feel more “real” than physical play.

For operators, this means the real work goes beyond mechanics and monetization. It is about designing meaningful rituals, creating spaces where players can inhabit roles, shaping emotional pacing, and offering a carefully directed version of reality that feels engaging yet responsible. The most successful platforms are those that understand not just how people play — but why they play, what they seek to feel, and how to build digital experiences that honor both excitement and trust.

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive more iGaming insights

Windows

Windows  macOS

macOS  iOS

iOS  Android

Android